Here's my latest piece for the South China Morning Post's Postmagazine. Say what you will about Chuwit ... he gives good quote. Pix by the talented Mr Cedric Arnold.

Super Pimp casts a long shadow over Bangkok. Wherever you turn, there he is, on televisions, newspapers, laptops, billboards, beetroot face contorted into its trademark twisted rictus, moustache aquiver with indignation and finger jabbing at some imagined outrage, ready to launch his next blow against corruption and injustice. One can almost imagine him swooping down from out of the sun, pimp cape flapping, patrolling the phalanx of fleshpots he built then disowned, eyes peeled for fresh perps.

Every metropolis gets the superhero it deserves. For the City of Angels, a town built on graft and grease and dirt and deals, on tortuous alliances and labyrinthine loyalties, internecine squabbles, snout-in-trough sweeteners and baht pro quo backscratching, who could be more suitable to step forward and save the day than the flawed, fabulously entertaining and batshit crazy crusader that is Chuwit Kamolvisit?

Thailand’s former massage parlour king and self-professed pimp turned Member of Parliament is reveling in his role as thorn in the government’s side, whistleblower and stirrer in chief, elephant in the room and motor-mouth maverick. After winning four seats in the recent election - a result that shocked many but revealed a deep-seated disgust amongst Bangkok’s middle class with the two big parties, the defeated Democrats, still headed up by faded poster boy Abhisit Vejajiva, and the governing Pheu Thai party, led by Yingluck Shinawatra, Thaksin’s sister, savior and stooge – Chuwit is still riding high in popularity polls. And with a deep-seated fear abroad that the blood-soaked belligerence of the red-shirts and yellow-shirts may not yet be consigned to history’s dustbin, locals are lapping up the comparatively light relief of the Chuwit sideshow while it lasts.

The pimp tag is not something that bothers him; rather, he has embraced it. “It’s OK. I was a pimp,’’ he says. “I did what I did in the past, I owned a lot of massage parlours. Of course I sold them all, but I can’t complain if people still want to call me pimp.

“Anyway, a politician is worse than a pimp, worse than a whore. I adore the whore. The whore trades something that she owns, her body, while the politician trades the country and what belongs to the people. So I say, go head, call me a pimp. I am Chuwit, Superpimp. Just don’t call me a politician."

It’s tempting to suggest he invest in a superfly mink-lined cape, perhaps a natty purple fedora and diamond-studded cane. As it is, his one concession to ghetto fabulous is his bull terrier, Motomoto, who was a prominent part of Chuwit’s election efforts and featured on the most entertaining of his talk-of-the-town campaign posters. “I used my dog as a symbol of honesty, loyalty, everything you can’t get from the politician,’’ he says.

His Lazarus-like return to politics surprised some, who had written him off after his last run at Bangkok governor ended in ignominy and bruised knuckles. Chuwit lost his temper on live television and punched and kicked a popular television anchor who had questioned his manliness.

His continued existence amazes many, who believe it’s a miracle that he hasn’t already been helped on to his next life by a hitman, given the fuming coterie of top cops, army generals and political powerbrokers he has embarrassed and cost large amounts of money. Now, his latest mission to expose Bangkok’s thriving illegal casinos – including threats this week to reveal a massive new establishment with an alleged key Hong Kong backer – has the entire city transfixed.

Chuwit, leader of the Rak Thailand Party, a month ago upstaged PM Yingluck’s maiden policy speech with his video-backed bombshell about a huge and professionally run casino in Bankgok’s Suttisan district operating a stone’s throw from a major police station. The fallout was extensive, provoking a frenzy of buck-passing and butt-covering, and eventually costing the police commissioner his job.

Now he’s at it again. This week, Chuwit said he would divulge details of a new mega-casino in Huay Kwang’s Mengjai district, which he claims is a joint venture between a former cabinet minister and a wealthy Hong Kong investor.

The key Hong Kong connection was a shadowy casino specialist he would only name as "Mr Tee" who had extensive experience in Macau and also at the casinos in the Cambodian border town of Poipet. The main local partner was reportedly a former cabinet minister, Chuwit said.

His latest claims are backed by the deputy prime minister and new Thai government vice tsar, Chalerm Yoobamrung, who said the government was keeping a close eye on illegal casinos under construction. He said the government was aware of a "significant" Hong Kong investment in Thailand's illegal gambling underworld.

"It's like a joint venture," Chuwit explains. "This guy Mr Tee, he has the international casino connections and the expertise. The local partner secures the premises and deals with the police and other officials. Mr Tee makes sure the security system, the computer and gaming technology, the lighting, the equipment and most importantly the croupiers, dealers, counters, cashiers and other key staff are all experienced casino employees. Because they know very well, if you have staff you can't trust they will rob you blind."

"To fit out one of these casinos takes up to two months and costs around 100 million baht [HK$25 million]," Chuwit said. "But ... they make a nightly profit of around 10 million baht. Police are getting fat off them and it looks like I'm the only one with enough guts to tell it like it is," he said. "You've got high rollers, roulette, baccarat, blackjack, bok dang, croupiers in uniforms, computerised equipment, money counters ... but to police it's obviously all invisible."

The new casino was located about 500 metres from the Meng Jai intersection in Huay Kwang district - ironically the same district where many of Chuwit's former massage parlours were located. He said the casino was ready to start operating. It was one of at least four being developed with Hong Kong backing.

When Chuwit told Parliament last month about a big illegal casino in Suttisan Road, Bang Sue district the disclosure led to the transfer of three senior police officers to inactive posts, a city-wide crackdown and a political firestorm, which claimed the scalp of National police chief Wichean Potephosree.

This week, acting national police chief Priewpan Damapong said police had searched the area and could find no gambling facility or evidence of one under construction. When apprised of this, Chuwit goes into paroxysms of laughter over the telephone. “Of course they are going to say that. These are the same cops who couldn’t see the Suttisan casino that was operating a couple of doors down from a major police station.’’

In what may be a warning shot over Chuwit’s bows, however, the Supreme Court this week ruled to seize Bt3.4 million from the MP in connection to his suspected involvement in a prostitution ring. A lower court and subsequent appellate review had previously ruled in Chuwit’s favour, but the high court took the view that he had failed to verify how the assets in question were acquired.

While Chuwit’s defence team argued that massage parlours were a legitimate business, the high court ruled there was enough evidence to support the parlours being used as a front for the sex trade, as evidenced by company records showing Bt 112,559 spent on condoms alone in 2002.

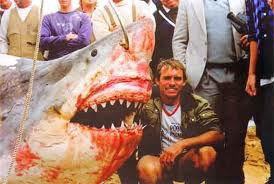

When I meet Chuwit on a drizzling Bangkok afternoon in the park that bears his name in Sukhumvit Soi 10, he is riding high on his first salvo about the illegal casinos but yet to launch his second strike. He has a gruff and affable charm but you sense a mercurial temper is simmering somewhere close to the surface.

It’s clear he gets a kick out of owning such a valuable piece of real estate and using it mainly as a private playground for his dog. “Yes, it’s true. You could say Motomoto is the owner here. One day I might do something here, but this is the last real prime undeveloped Sukhumvit Rd site. So I am happy to sit on it for a while.’’

Chuwit says he was surprised to win as many as four seats in the election, but not surprised that he himself was comfortably elected. “In my campaign, I presented myself as boring. Thai politicians play politics too much. They talk, talk, talk, but never do anything.’’

Fighting corruption was Chuwit’s main campaign promise. “Corruption in Thailand is supported by the officials, the politicians, the police, the system. Nobody wants to talk. It’s a big issue in this country.’’ Which might seem a bit rich coming from a man who gleefully detailed the staggering amount of bribes in cash and other largesse he paid to all manner of Thai officials to facilitate his business in its heyday.

Chuwit strokes his moustache and looks to the heavens. “Look, have you seen the movie ‘Catch Me If You Can? You’re not going to catch a crook by using a good guy. I am the one who knows the (corruption) process better than anyone. So I can make myself useful now to expose corruption. ‘’ It takes a thief to catch a thief? “Exactly!’’

Can one man really accomplish anything? “Corruption is so strong in Thailand I don’t think it will ever change. I’m not saying I can do anything. But I have vowed to try.’’

The last time Chuwit was making these kind of waves was in 2004, where he kept Bangkok on the edge of its seats with lurid revelations of police corruption relating to his massage parlour business. The sensationally sordid saga of sex, bribes and videotape hit the front pages when Chuwit revealed that he was paying senior police from four of Bangkok’s biggest police districts over 12 million baht in bribes per month (not a bad sweetener when you consider the average constable’s salary barely breaks four figures). Chuwit also spoke of how he showered the officers with trays of Rolex watches shipped in from Hong Kong and crates of the finest French vintages.

He didn’t name names, but said he had a list prepared to do just that in the event of his untimely demise, not to mention lurid details of the peculiar sexual proclivities of some of the city’s top cops, some reportedly captured on camera. His tirade was prompted by what he deemed a betrayal by men he had made extremely wealthy and who he paid to protect him. This followed the infamous January 2004 midnight raid in which armed thugs reduced to rubble a motley collection of beer bars and small businesses in what used to be known as Sukhumvit Square. The raid shocked Bangkok, embarrassed the police and angered the government. Chuwit had recently bought the land in question, although he denied authorising the raid and claimed it was orchestrated by a man he had agreed to lease the land to. (Later, in the face of a mounting furore, he magnanimously decided not to develop the land but to turn it into a public park).

A warrant was issued for Chuwit’s arrest, and he found himself dragged off to spend a month in jail pending formal charges. At the same time, he was also charged with employing three underage girls at one of the six massage parlours operated by his Davis Group.

“Of course I felt betrayed,’’ says Chuwit. “I felt crazy and frustrated. All the money I have paid to police and then they stabbed me in the back. So I decided to do what no one has dared before, to tell the Thai public what really goes on.’’

Things took their first weird twist when Chuwit went missing days after his initial revelations. Debate raged as to whether he was already dead or had fled the country. Three days later, a wild-eyed Chuwit called a press conference in his pyjamas in a Bangkok hospital, shouting and rambling as he claimed he had been kidnapped, drugged and held hostage by masked men.

Then National police chief Sant Sarutanont, before even beginning to investigate the claims, declared that he didn’t for a minute believe the tale and said Chuwit had staged the event to gain public sympathy. He also set up a fact-finding panel which within a matter of days found there was no substance to the claims of massive bribe-taking by officers at Huay Kwang, Makkasan, Suttisan and Wang Thonglang police stations.

But Chuwit was just getting warmed up. He produced hundreds of pages of signatures which he said belonged to police who received free services at his parlours, prompting then Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, a former policeman himself, to call for the entire Huay Kwang station to be transferred. Thaksin promised that he’d clean up the force within six months. A new panel was set up to probe police corruption, headed by Noppadol Somboonsup, director general of the recently-formed Special Investigation Department, the Thai version of America’s FBI.

Chuwit then began to feed the press with a daily diet of teasers and stunts. He released the initials of senior officers who got the biggest bribes, prompting flurries of speculation. He then revealed a detailed list of bribes paid by rank, ranging from 80,000 baht per month for Superintendents down to 2,000 for deputy chief inspectors. He claimed he had paid 300,000 in bribes to prison staff while incarcerated, including 5,000 baht for fried rice and 10,000 baht for a proper shower.

He donated 13 coffins to a Bangkok charity and dedicated them to “bad bribe-takers who don’t accept the truth’’. He appeared in one mass circulation newspaper bare-chested and lifting dumbbells, to “get in shape for the battle’’. He tried and failed to present a list to the Prime Minister with the names of 1,000 allegedly corrupt Bangkok police officers. And he took the press on a tour of “Suite Five’’ at his Copacabana parlour, a Roccoco riot of marble and gilt which could accommodate 15 guests and cost millions of baht to decorate. “I lose hundreds of thousands a night on this suite alone,’’ he complained. “It’s always full of police, who want free drinks and free girls.’’

If the figurative spotlight wasn’t enough, Chuwit then took to the boards for a one-night talk show at the Bangkok Playhouse, which was an instant sell-out despite it’s somewhat self-pitying title: "Chuwit: Alone and Shabby''. He penned a quickie book, “The Golden Bath: the Origin of Sex and Every Scandalous Thing'', in which he reminisced about his younger years as a playboy, trying to spend as much of his family’s textile fortune as he could while fancying himself the Thai Hugh Hefner.

system had malfunctioned on the night in question.

“Yes, I was a playboy,’’ Chuwit chuckles, as we stroll the lush manicured paths of his park. His father was born in Hong Kong and his mother was Thai. After returning from San Diego, California with a Master of Business Administration, Chuwit was eager to put his new business theories into practice. “I was 30 years old. I wanted to be surrounded with girls. What’s wrong? Making big money. So what?

“I liked massage parlours, but the old ones here used to be done in a very old fashioned way. It was all rush rush, like going to McDonalds. Maybe men don’t want McDonalds. Maybe they want a Chinese banquet. To relax, listen to music, have a drink, take your time. So I changed the whole idea to make the massage parlours more of an entertainment venue.’’ He laughs. “My places were better than anything you’d get in Vegas. I went to a lap dancing place in Las Vegas once. You had to listen to a 10 minute speech on the rules, you cannot touch the body, you cannot do this or that. You can drink though. And tip. I thought it was ridiculous.

“So all I did was give men what they want.’’ He fixes me with his most steely superhero squint from beneath famously furrowed brow. “The sex business is not wrong. People are wrong.’’

Chuwit made a modest fortune in real estate in Bangkok after returning from his US studies, and bought his first massage parlour licence in the late 1980s. “It was good for 106 rooms. I had the land, I had the licence, so I opened Victoria’s Secret, around Ratchadaphisek and Rama 9 roads. Boy, did I start making money. Do you believe it? I was making a million baht in cash every night. And from the first day, the police were there with their hands out.’’

He opened Emmanuelle, then Honolulu, then Copacabana, all of them sumptuous exercises in nouveau riche excess, where some of Thailand’s most beautiful women sat wearing numbers behind glass walls waiting to be chosen by the rich and powerful. “Is it prostitution? Of course. I provide the classy place, the beautiful girls, the booze, the atmosphere. When someone goes to a room, you can’t stop them having sex. But prostitution is illegal, so none of it works without the cops looking after you.’’

An astute political animal, Chuwit goes out on quite a limb by predicting that Thaksin will be back in Thailand by the end of the year. “Look at them all now,’’ he says, referring to the Pheu Thai party movers and shakers. “They are moving all the pieces around the board now, getting the right people into place to force an amnesty and secure his return.’’

Chuwit swears that he no longer has any interest, financial or moral, in the flesh trade and says his only business these days is his Davis Hotel group and his real estate holdings. Last time I interviewed him, seven years ago, the Anti-Money Laundering Office had just frozen his assets. This time, it’s the court order – although 3.5 million baht is chump change to someone with a fortune estimated at around 250 million baht.

We continue to wander about the park. Joggers, strollers and office refugees beam and rush up to say hello, we love you, we voted for you, keep the bastards honest. It’s bizarre in the extreme given his history as a virtuoso corruptor but there’s no denying he has tapped a nerve. His macho image and undeniable charisma probably don’t hurt either. As he chats with another admirer, I glance around the gardens and wonder if he has some souped up superhero-mobile in an underground garage, or a pole to slide down to a graft-busting nerve centre.

So what is the next crusade for Superpimp once all the illegal casinos have been exposed? “I’m not superman. I’m not a hero,’’ he says. “People think I can do something but really, all I can do is speak up. Talk about the things other people are scared to. In Thailand, everybody knows, but nobody talks. There are lots of issues for me to talk about. Corruption. Drugs.

“But it’s all about timing and balance. I can’t be in the news every day. People will get sick of me. So I will pick my battles and know when it’s time to speak and when it’s time to stop.’’

Chuwit turned 50 in August and he admits it was a milestone. “You do stop and think about life. See over there on that table? There is a catalogue of yachts. I look at it every day. One day, I will buy the yacht. That is my goal. That’s happiness. There is no happiness in politics.’’

Perhaps not, except for the fact that politics may be all that’s keeping him alive. “Yes it’s true, I’m in the spotlight now and to an extent my high profile protects me. When I’m not in that spotlight, I will have to leave Thailand. It will be too risky here. Life is cheap, and I have too many enemies. You can hire a hitman for 200,000 baht. So I have to be focused all the time. It’s the only way to survive. If you lose that focus, you die.’’

It’s hard out there for a pimp.